What is a utility patent specification? And why is it critical for patent applications? Below, we lay out the structure of a utility patent specification and explain each part’s function.

The utility patent specification is one of the critical documents in a patent application that we at Alloy Patent Law prepare for our clients. Without the specification, inventors’ utility patent applications have no chance to meet the statutory requirements for utility patents.

However, outside of the utility patent application process, the specification also plays an important role in utility patent litigation. In the intellectual property litigation world, one of the key tactics in utility patent infringement defense is to invalidate an issued patent. One way to do this is for the accused infringer to challenge the validity of an issued patent, and then show evidence that the patent examiner did not consider certain prior art that would have invalidated the patent. While challenged utility patents are assumed to be valid, thereby requiring a higher burden of proof to show invalidity, a poorly written specification may present a higher chance of a post-issuance invalidation.

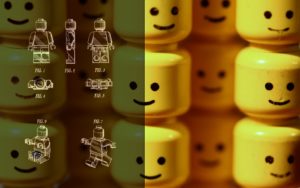

Understanding what a utility patent specification is and what it contains requires a quick explanation of the purpose of patents. In a sense, patents can be seen as a quid pro quo between the inventor and the U.S. government. The government offers the inventor certain exclusive rights to their invention if the inventor, through the specification, drawings, and claims, discloses their invention to the public. When an inventor’s patent application is approved by the patent and trademark office resulting in a patent, the inventor gains an intangible intellectual property that they may exploit. In the case of patents, the exclusive rights gained from a patent for their intellectual property can lead to great financial gain.

The exclusive rights are not forever for patents though. For a United States patent, the exclusive rights can last only for a maximum of 20 years from the filing date of the utility patent application (or priority filing date from a provisional patent application). Also, for a United States patent, after a patent issues, a patent holder must periodically pay maintenance fees, with the first fee due three and a half years from the filing date, the second due seven and a half years from the filing date, and the final due eleven and a half years from the filing date.

The full breadth of requirements for the patent application specification can be found in 35 U.S.C. 112(a), which states, “The specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the same, and shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor or joint inventor of carrying out the invention.” In simpler terms, the specification must have a written description of what the invention is, it must enable a person having ordinary skill in the field to make and use the invention, and it must show what the inventor considers the best mode to carry out the invention.

The specification accomplishes these goals in the various sections described below.

The Components of a Specification

Title of the Invention

While not specifically listed as a requirement, the invention title serves the purpose of identifying what the invention is. Special care must be taken when naming inventions. In the patent world, any word in the specification may be used against you, and this includes the invention title. Effective patent attorneys understand this, and make sure to use an invention title that does not limit the invention’s applicability while still accurately identifying what the invention is.

Name of the Inventor

This simply identifies the inventor or co-inventors for the invention in the patent application.

Cross-References to Related Patent Applications (Optional)

Inventions in a patent application can often contain multiple inventive concepts. When this situation occurs, each inventive concept typically requires its own utility patent application. Cross-references are made to other utility patents or utility patent applications that are related to the invention seeking patent protection.

Field of the Disclosure

The first of the required sections in a utility patent specification, the Field of the Disclosure is a one-sentence statement that declares what field of practice the invention in the patent application belongs to. Its purpose is simple: identifying the field of the disclosure allows the patent and trademark office to properly match the patent application to the appropriate patent examiner.

Background of the Invention

The Background of the Invention, the second required section in a utility patent specification, is written to accomplish two goals.

The first goal of the Background of the Invention, as the name would suggest, is to provide background information related to the invention for which patent protection is being sought. This section discusses both the industry and the available prior art related to the invention, and in doing so leads to the second – and arguably more important – goal of the Background of the Invention, to present the problem that the invention seeks to solve.

Thus, an effective Background of the Invention presents the relevant information pertaining to the invention and the field it belongs to, states clearly the problem that the invention will solve, presents the relevant prior art, and discusses why the prior art is insufficient to solve the problem that the invention will solve. A patent application that does not clearly state the problem will likely have issues in the prosecution of the case.

Summary of the Invention

The Summary of the Invention has a simple goal: present the solution for the problem that the Background of the Invention presented. In practice, an effective utility patent Summary of the Invention opens with a single statement that efficiently restates the problem detailed in the Background of the Invention and presents the invention as the solution. From this opening, patent lawyers typically take one of two approaches for the summary.

The first approach entails the patent attorney restating the language of the claims as the summary of the invention. This approach may be applicable to inventions having such narrowly drafted claims that what the invention is may easily be discernible from the claim(s) language. If the claims language is able to define what the inventive solution to the problem is, then this claims restatement approach is acceptable.

However, most claims language is drafted broadly to maximize the scope of exclusive rights for the patent owner. Accordingly, the second approach only makes use of claims language in the summary if its use serves the purpose of defining what the solution is to the problem presented. This second approach is more narrative in nature, focusing on what the invention does to solve the problem. This approach ensures that the summary meets the statutory requirements for definiteness, a requirement that the former approach may experience difficulty meeting.

Regardless of the approach, mindful patent lawyers should also include language to remind the patent examiner at the patent and trademark office that the descriptions are for illustrative purpose only to help the examiner understand the invention, is in no way limiting to the scope of the invention, and that the claims ultimately determine the scope of reach for the invention.

Brief Description of the Drawings

The fourth requirement, The Brief Description of the Drawings, works in tandem with the fifth requirement, the Detailed Description of the Invention, to meet the enablement requirement for a United States patent. The Brief Description of the Drawings are simply single-sentence statements – for example: “a top-right perspective view of an invention” – for each figure. These descriptions help the examiner understand the patent drawings that are submitted for the utility patent application.

Detailed Description of the Invention

As mentioned earlier, the fifth required section, the Detailed Description of the Invention, works in tandem with the patent drawings and its brief descriptions to meet the enablement requirement. This means that in the patent application, the description must allow a person having ordinary skill in the art to make and use the invention. However, the description must also clearly describe what the invention is, and it must describe the best mode that is contemplated by the inventor of carrying out the invention. Outside of these three requirements, a utility patent application may also provide descriptions for alternative embodiments to help illustrate what the invention is to the examiner. With respect to formatting, patent lawyers have wide leeway to be as descriptive as possible. Whereas with claims patent lawyers should aim to draft as broadly as possible, with the detailed description, patent lawyers should instead aim for specificity, always keeping in mind that the totality of the patent application is what the patent and trade office examines.

A Quick Aside for Claims – Are the Claims part of the Specification?

While researching for this article, I noticed some disagreement in the patent law world as to whether the claims are part of the specification.

The claims of utility patents define the legal boundaries of an invention. Anything within those claimed boundaries of a utility patent is what is protected against infringers. Any matter that falls outside the claims’ boundaries is not protected.

The disagreement among patent lawyers and patent law firms seem to stem from 35 U.S.C. 112(b), which says, “The specification shall conclude with one or more claims particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter which the inventor or a joint inventor regards as the invention.” Because the statute reads, “The specification shall conclude with one or more claims…,” it is not uncommon for a patent attorney to take the position that the claims are part of the specification. Other patent law firms, like Alloy Patent Law, take the position that the specification is separate from the claims and is defined in 35 U.S.C. 112(a), as described above. Ultimately, either position is acceptable, as standard practice dictates that the claims are placed on a separate page after the specification.

The Abstract

Finally, appended on a separate page after the specification and claims is the abstract, a brief statement that concisely summarizes the invention. While no guidance on length is provided, the typical abstract should concisely summarize the invention in 150 words or less. In some instances, the abstract is not appended to the end of the patent application specification, and is instead added to the beginning. However, as with the claims, the abstract is not part of the specification.

Conclusion

We at Alloy Patent Law recognize that the parts of a patent specification can be confusing to inventors new to the patent application process. Patent law is, after all, one of the more complicated legal practices in intellectual property law. We hope this brief explanation helps the clients of Alloy Patent Law understand each of the five major parts of a specification, as the process of preparing the specification for utility patents is highly collaborative for the inventor and patent attorney.

If you are an inventor seeking to gain protection for your intellectual property, schedule a free consult with Walker, our expert patent attorney.